‘Scared as Hell’: This Judge’s Father Told Him No One Would Hire a Gay Lawyer

February 20, 2019

By Robert Storace

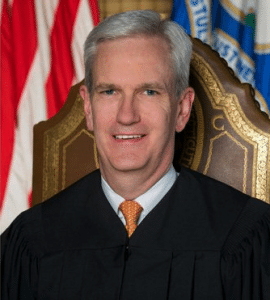

Connecticut Supreme Court Associate Justice Andrew McDonald discusses evolving public attitudes toward gay attorneys and judges.

As a young man, Andrew McDonald‘s father gave him a warning: No client would want to work with a homosexual lawyer.

As a young man, Andrew McDonald‘s father gave him a warning: No client would want to work with a homosexual lawyer.

His father was wrong. Not only did McDonald find work, but in the years that followed he rose to the pinnacle of his profession to sit as a jurist in Connecticut’s highest court.

But on that day in 1994, when McDonald came out to his father as a 28-year-old gay man, things looked bleak.

“When I told my dad, he was surprised, and he counseled me as best he could, as he understood the world at that time,” said McDonald, now an associate justice on the Connecticut Supreme Court.

At the time, the future justice was still a third-year associate at Pullman & Comley, the powerhouse firm that’s emerged as one of the largest in Connecticut. His father, Alex, had grown up in the 1940s and 1950s, when homosexuality was illegal and widely viewed as immoral. It was an act of love, McDonald said, for his father to question whether the young lawyer would survive in the legal profession.

He remembers their conversation vividly.

“He told me that I’d have to figure out what Plan B would be for my life because, as he understood the times, no law firm would make an openly gay man a partner in their law firm because clients would not tolerate it,” McDonald said. “Secondarily, he knew how important public service was to me and he told me that if I ever came out publicly, voters would react negatively and I’d never hold any public position of trust.”

McDonald ended up thriving as a lawyer and a public servant.

He became a partner at the firm and ended up getting elected state senator in 2003, despite negative comments about his sexuality. The Stamford native then served as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee and in 2013 was named to sit on the state’s highest court as an associate on the Connecticut Supreme Court.

Many in the LGBTQ community now see McDonald, 52, as a trailblazer.

Jessica Grossarth Kennedy, now a partner at Pullman & Comley, started at that firm in 2002, and said she looked at McDonald and partner John Stafstrom as role models.

“I saw that the firm treated them no differently than anyone else and, having seen that, it gave me confidence to know that the firm would treat me the same if I came out,” she said.

So about a year after joining the firm, Grossarth Kennedy did just that.

Her decision is a sign of how things have changed since the justice was a young attorney.

“Homosexual relations were criminal in 49 of 50 states when I was born [in 1966], so that kind of gives you a launching point for the arch of my life,” McDonald said. “My dad was born in 1929 and he lived through the McCarthy era where, amongst other things, it was not only a hunt for communists, but McCarthy also targeted homosexuals. His mission was to ferret out homosexuals from government service or positions of public trust.”

Your Journey Is Yours Alone

McDonald said his father eventually “came around” adding, “nothing changes your mind quicker than seeing someone you love being treated unfairly.”

McDonald, who has spoken publicly on the issue on several occasions, said he “was scared as hell” when he came out at the firm.

“But when I did, I was warmly embraced,” he said. “What my father told me was lurking in the back of my head as I did not know anyone at that time who was openly gay at any law firm. I thought it was like jumping into the abyss, when actually it was like jumping into an embrace.”

Many in the legal profession who are gay have approached McDonald for advice on whether to come out and how that could impact their career.

“My recommendation to those in the closet is, first, your journey is yours alone,” McDonald said. “It does not, though, mean you have to walk it alone. There are resources out there ready and willing to support you in coming out in this profession.”

Now, industry groups across the country include voluntary bar associations for LGBTQ attorneys. And changing federal and state laws granted marriage and other civil rights reflect changing public views toward a once-marginalized demographic.

“Slowly, but surely, attitudes change as people see gay people become attorneys and judges and every other aspect of the community,” McDonald said. “It debunks the stereotypes and mythology around the capabilities and trustworthiness of the LGBT members of the community.”

Decades ago, McDonald said, because of stereotypes, “The only people I understood to be gay were Liberace and Elton John and hairdressers and florists.”

But these days in Connecticut, McDonald is one of six openly gay judges. And large firms, including his former employers at Pullman & Comley, have embraced openly gay partners.

“I believe there are more openly LGBT judges in Connecticut than there are gay partners in law firms,” McDonald said, adding that be believes that statistic will soon change.

He said, “We are light-years from where we started, but we still have light-years to go.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.